Russian Dolls: Originally From Japan

©Laetitia Hébert

The archetypal Russian souvenir, Matryoshka dolls are so intrinsically linked to Russia that their real origin has been forgotten. The dolls are, in fact, Japanese, and named kokeshi.

A renowned Russian industrialist named Savva Mamontov went on his travels to Japan and, in the late 1890s, brought back one of the seven deities of happiness. According to Japanese tradition, the seven deities arrive in the city for the new year and distribute gifts to those deserving of them. Inspired by the figurine, painter Serguei Malioutine picked up his brushes and created a Russian version, depicting not a deity but the reassuring face of a peasant woman containing her offspring, all the way down to a newborn. Nicknamed matryoshka, derived from the Russian female first name Matriona and evoking an image of a rustic, robust countrydweller, the doll quickly won the hearts of Russians, especially children.

©Cha già José

As well as being a toy, the matryoshka was also used to teach manual dexterity and the first elements of maths, while making children aware of family through the protective mother figure. The very first Russian doll made in 1890 even won the bronze medal at the 1900 Paris Universal Exhibition owing to its innocent features and the quality of its production.

The nested doll’s origins lie firmly in Japan, however, and it displays an undeniable level of traditional craftsmanship which is a source of fascination for Laetitia Hébert. After discovering kokeshi while living in Japan for five years, in 2017 she decided to open folkeshi.com, a shop selling only Japanese dolls to ‘support Japanese artisans and offer them visibility abroad so that they can continue their activity in a sustainable manner’, she explains.

Although the term kokeshi is not meaningful in hiragana, its more recent interpretation in kanji combines the terms ko for ‘child’ and keshi meaning ‘remove’, creating the idea of ‘making the child disappear’. However, Laetitia Hébert adds, ‘when writing about kokeshi, Japanese authors have all put this link to infanticide aside, because the documents supporting this idea all date back to after the Second World War, that is 130 years after the appearance of the first kokeshi, and refer to fictional sources’.

©Laetitia Hébert

Originally made as toys for girls, kokeshi have also become decorative objects and continue to be made following the same method, still by the hand of a master. After selecting untreated cherry wood, pear tree wood or maple depending on the location, the artisan removes the bark and dries it for a period of one to five years. The wood is then cut into logs, and then the two pieces that make up the doll, one for the head and the other for the body, are sanded, painted, assembled and waxed before the final step: the signature of the artist on the doll, the mark of unique expertise.

This painstaking work was formerly linked to the original place of manufacture, Tohoku, a rural region in northern Japan which is ‘still seen as the incarnation of a lost Japan’, explains Laetitia Hébert. Today, kokeshi are more evocative of the work of artisans with a delicate touch, but also testify to a heritage which is dying out. At this moment, just 180 artisans are still striving to continue their activity, despite the fact that most of them are over 65 years of age. ‘The few young people who preserve the tradition do so out of familial pride and the belief that kokeshi must continue to exist’, states Laetitia Hébert, who tirelessly continues to export Japanese dolls to all four corners of the globe and support a handicraft which otherwise risks being lost forever.

©Laetitia Hébert

©Laetitia Hébert

TRENDING

-

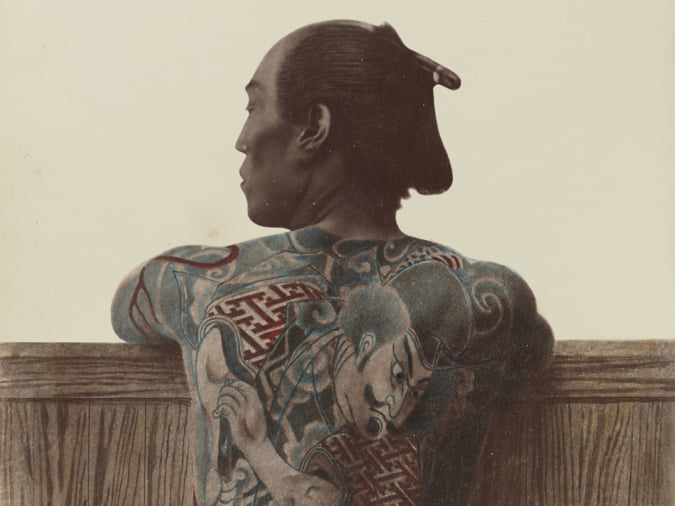

Colour Photos of Yakuza Tattoos from the Meiji Period

19th-century photographs have captured the usually hidden tattoos that covered the bodies of the members of Japanese organised crime gangs.

-

The Tattoos that Marked the Criminals of the Edo Period

Traditional tattoos were strong signifiers; murderers had head tattoos, while theft might result in an arm tattoo.

-

The Nobu Empire, the Fruit of the Friendship between the Chef and Robert De Niro

The two men are partners in Nobu Hospitality, a luxury restaurant and hotel brand that has become a global success.

-

Hayao Miyazaki, the Man Who Adored Women

The renowned director places strong female characters at the heart of his work, characters who defy the clichés rife in animated films.

-

The Tradition of the Black Eggs of Mount Hakone

In the volcanic valley of Owakudani, curious looking black eggs with beneficial properties are cooked in the sulphurous waters.